How do I... - Tuesday 18 February 2025

Our highlights to help you in your researches

4 types of Highlights to help you:

| Write your thesis | Good to know |

|---|---|

Rate this content

How do I... - Tuesday 26 September 2023

Searching for information with AI (Part 2): conversational agents

(Part 1: recommendations and search engines)

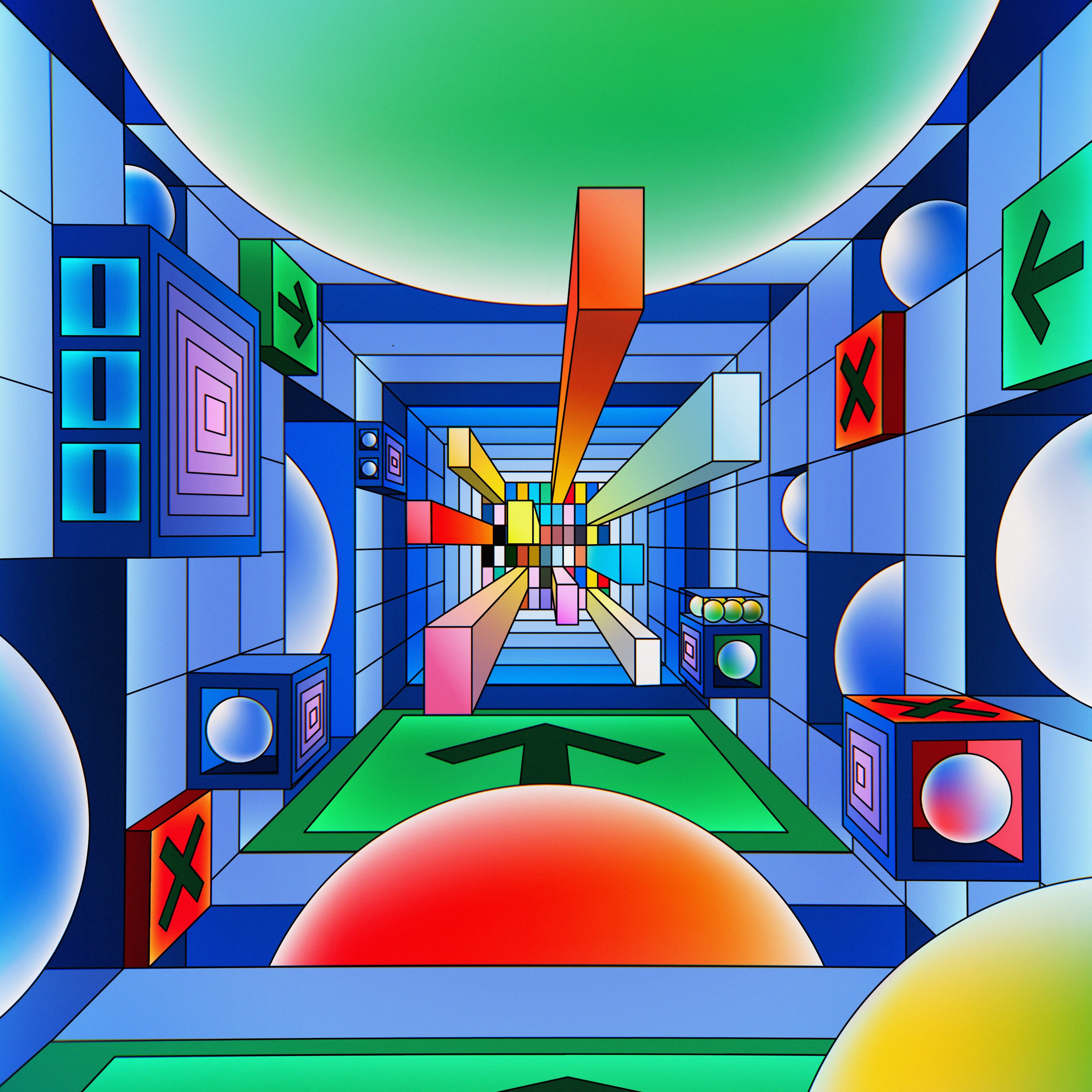

Coming to the spotlight at the end of 2022 with the general public release of ChatGPT3.5, then 4 in spring 2023, conversational agents are tools based on the analysis of large corpora of documents and statistical probabilities for text generation (GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer). The term generative AI is used more generally, particularly for content other than text: computer code, mathematical formulas, images, videos, etc.

Given the tool's versatility in processing text, it can be used at "every stage of the intelligence process, from identifying needs, to sourcing, to analysis." For example, through semantic analysis, the tool can summarize one or more texts and extract the key ideas to generate keywords, which can then be used to search for other documents. The tool can also lay the foundations for market research by locating competitors, identifying their characteristics, drawing up profiles, etc.

To complete the picture, here's an overview of other tools derived from or inspired by ChatGPT that can be useful for finding information, in the form of web applications or browser extensions:

- Youtubesummary with chatGPT to transcribe and summarize Youtube videos

- Gimme Summary AI to summarize a web page

- LegiGPT for basic legal information (in French)

The ChaptGPT 4 tool is available free of charge, but only after creating a Microsoft account, via the Bing Chat tool: go to bing.com/new with the Edge browser.

Querying them using prompts

Conversational agents answer queries using prompts, i.e. instructions formulated as precisely as possible. The more precisely the context of the information query is defined in the instructions given to the AI, the more relevant its response will be. For example, specify the profile of the person requesting the information, and their level of knowledge and understanding of the subject. Indicate the desired output format, to save time when formatting the information.

Using generative A.I. to "produce" information

In addition to information retrieval in the form of text, figures or images, so-called generative AI can of course also be used to produce content of the same type. This practice raises a number of ethical issues, the most obvious of which relate to intellectual property and academic integrity. While it is accepted, for example, that AI cannot be cited as an author in the true sense of the term, this does not mean that it cannot be cited as a writing aid for a dissertation, article, thesis, etc. The scientific and technical information department of CIRAD (Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement) makes this clear:

“Le Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) a rédigé une note de position (Authorship and AI tools - COPE position statement, version 1, 13/02/2023) soulignant que ces outils ne sont pas assimilables à des auteurs, que ces derniers doivent décrire comment ils les emploient et qu’ils restent responsables du contenu de leur publication, quelle que soit la manière dont ils l’ont produit.”

Images

Numerous copyright issues potentially arise, but the framework is evolving: there is no person in the legal sense who creates content, and therefore no author, but neither are there any commercial uses made possible by a free license or assignment of rights. The use of AI-generated content should therefore initially be tolerated on a not-for-profit basis, unless the tool specifies otherwise, particularly in the case of paid professional use. There is also a potential problem of cascading plagiarism: the tool may infringe copyright by "training" itself on a corpus of protected works, whose features it then reproduces too distinctly, by providing its users with images that amount to "style theft".

Texts (including translations)

A good practice is not to use a text generator without mentioning it, or in excessive quantities, as this would violate academic ethics, as seen above. This also means mentioning the use of a machine translation tool, even for text that has been edited.

Text-to-speech

This use of artificial intelligence for automatic language analysis makes it possible to switch from written to spoken text and vice versa, and can be useful both for transcribing interviews and for facilitating access to various textual contents. However, any text copied into a free web-based tool such as TTSreader may be reused by the tool's designers to improve it, so you need to take care to protect personal and sensitive data. Be sure to read the terms and conditions of each tool carefully.

Some ethical issues

Beyond potential infringements of copyright or academic ethics, text-generating tools pose problems in terms of the quality of the information provided. For example, ChatGPT does not mention its sources in its answers, while basing itself on a limited corpus that has not been updated beyond 2021. It can "invent facts", enabling ill-intentioned people to spread disinformation under an air of accomplished veracity. The ESSEC Learning Center is here to help you deal with these pitfalls.

The search for and production of information using tools based on artificial intelligence is indeed a rapidly evolving field, to be monitored as much from the point of view of tools and practices as from that of regulations and social developments in the broadest sense.

For further information, Semantic Scholar and Typeset.io, are two AI-assisted search tools that can be used for keyword formulation and results analysis.

Sources

- Eugène, Matthieu. “ChatGPT : notre guide pour créer les meilleurs prompts.” BDM, April 17, 2023.

- Fovet-Rabot, Cécile, and Marie-Claude Deboin. “Définir Les Auteurs d’une Publication Scientifique.” CIRAD, 2014.

- Khan, Lina M. “Opinion | Lina Khan: We Must Regulate A.I. Here’s How.” The New York Times, May 3, 2023, sec. Opinion.

Rate this content

How do I... - Friday 22 September 2023

Searching for information with AI (Part 1): recommendations and search engines

The objective of this zoom is to communicate on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in a very general way, and on some of the functionalities it already provides for information research.

Definition of A.I.

Here we use two definitions quoted in the article “Defining artificial intelligence for librarians” :

- the OECD definition : "Artificial intelligence (AI) is ‘a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments. AI systems are designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy’". (OECD, 2020).

- and the European Commission's definition, which is also very general : "Simply put, AI is a collection of technologies that combines data, algorithms and computing power". (European Commission, 2020: 2).

To go beyond these simple definitions, you can consult the following works at ESSEC's K-lab:

|

Agrawal, Ajay Bansidhar. Prediction Machines : the Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2018. |

|

Crawford, Kate. Atlas of AI : Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021. |

And for a facilitated understanding of A.I. in relation to social issues, consult the free online guide:

|

Onuoha, Mimi and Nucera, Diana. A people's guide to AI. A People’s Guide Press, 2018 |

Possible uses of AI for information retrieval

The article “Defining artificial intelligence for librarians” cites three examples of AI applications in library services for their users.

- The first is the use of automated rankings and recommendations in metasearch tools such as Discovery.

- The second is the implementation of conversational robots to interact with library users, answering their questions and guiding them in the use of services and resources.

- The third use is the automation of scientific literature reviews in order to keep up with the scale and accelerating pace of publications.

These uses are not yet very widespread for reasons of cost and complexity of implementation, but the ESSEC Learning Centre is keeping a close eye on new tools and functions of this type.

Recommendations

Recommendations have been part of the information landscape for several years. They are based on the analysis of recurring features in the document consultation paths of one or more people, in an attempt to predict what might meet their specific information needs. An example of the reasoned application of this type of technique is provided by the CAIRN database.

First of all, it should be pointed out that this recommendation service can only be accessed once an account has been created, which involves the management of personal data. So it's important to appreciate the value of a service that requires a counterpart that is far from trivial. In this sense, A.I. can put the spotlight even more firmly on ethical issues that were already being raised in social networks and free web services monetised by targeted advertising.

The recommendation criteria used by CAIRN are explicit and limited to a few, some of which can be configured by the user: semantic proximity, 'bounces' on authors referenced in publications already consulted, other articles read by readers of the same article as you. The information provider points out that "the algorithm cannot replace the human recommendation, drawn up by an expert in the discipline or field concerned.”

Search engines

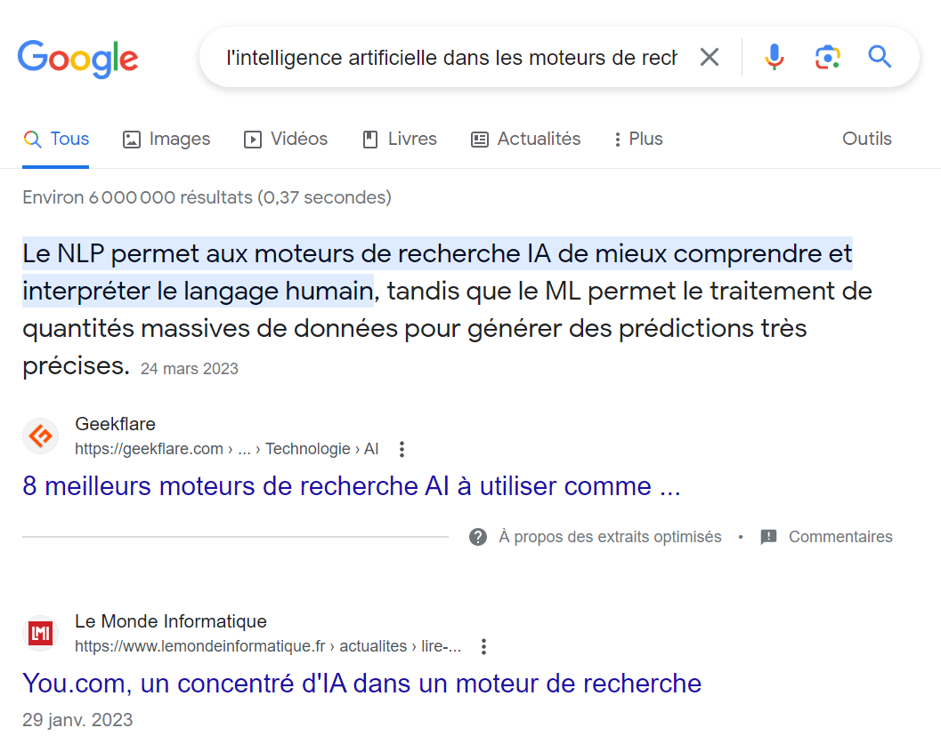

For several years now, search engines have been relying on machine learning to deliver the best answers to their users' queries. These queries tend more and more to be formulated in natural language, and less and less in combinations of keywords, search equations with Boolean operators or the equivalent of an advanced search with precise search fields. Nevertheless, this approach is still relevant.

The various uses of A.I. in search engines are aimed on the one hand at de-duplicating results and eliminating those that have no informational value, while at the same time classifying results in an order of relevance that is constantly evolving with new criteria. It is also useful for search engines such as Google to disambiguate the terms used, in order to better decipher natural language. A classic example is a search on the term "orange", for which it will be necessary to determine whether it refers to the city, the colour, the fruit, the brand, etc. This refinement of meaning enables the tool to try to "understand and detect the user's intention" when he enters his query in the search box. This increases the impression of relevance given by the results provided by the search engine, without even involving the famous conversational agents that are currently the talk of the town.

The second part of this highlight covers conversational agents.

Sources:

- “AI-Principles Overview - OECD.AI.” Accessed September 19, 2023. https://oecd.ai/en/principles.

- Anne-Marie. “Google n’est plus un moteur de recherche ni de réponses, mais un assistant virtuel.” Bases & Netsources. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.bases-netsources.com/articles-netsources/google-n-est-plus-un-moteur-de-recherche-ni-de-reponses-mais-un-assistant-virtuel.

- Cox, Andrew M., and Suvodeep Mazumdar. “Defining Artificial Intelligence for Librarians.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, December 22, 2022, 09610006221142029. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006221142029.

- Vathaire, Jean-Baptiste de. “Maîtriser l’algorithme pour favoriser les interactions : du bon usage des recommandations personnalisées. Utilisation et approche de l’IA par le portail Cairn.info.” I2D - Information, données & documents 1, no. 1 (2022): 50–56. https://doi.org/10.3917/i2d.221.0050.

Rate this content

How do I... - Friday 02 June 2023

Legal information research

This zoom is a reminder, for non-lawyers, of the main principles governing the law, and more specifically commercial law: where the law is written, how it is applied, how it is accessed... This zoom does not cover legal, administrative and financial information for companies, for which resources such as Infogreffe, Orbis and Diane can be consulted.

Let's take a concrete case of legal information research for the launch of a new product in the alternative health sector, herbal medicine, in two European countries simultaneously: France and Greece.

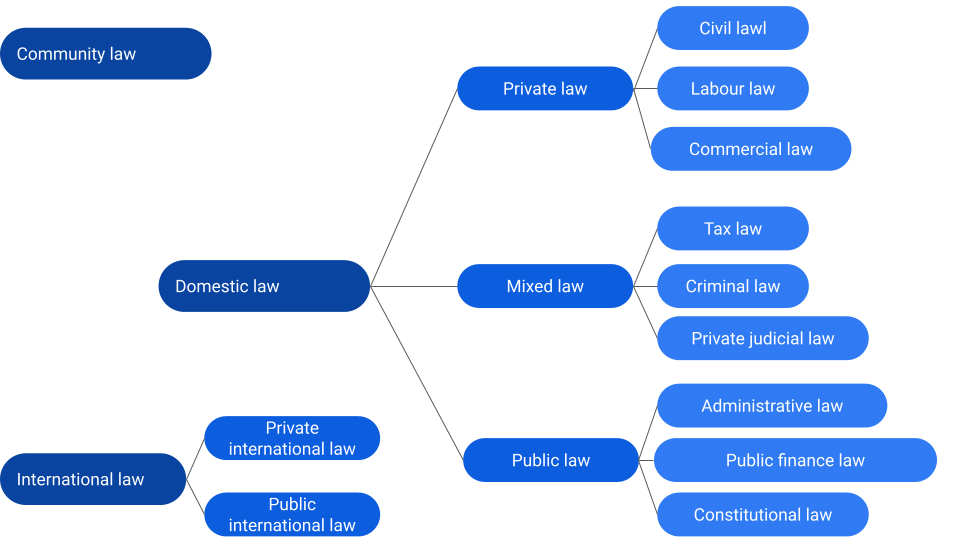

Broadly speaking, there are several branches of law, present in different geographical areas.

- International law: rules governing international relations.

- Community law: rules applying to the institutions, member states and nationals of the European Union.

- National domestic law: the body of legal rules governing social relations within a given state.

The diagram of the different branches of law below was inspired by the Université Numérique Juridique Francophone (UNJF) website, which outlines the main legal concepts.

There are different sources of law:

- Legislation: all normative texts = laws and regulations.

- Case law: all legal decisions handed down by constitutional, judicial or administrative jurisdictions

- Dalloz or Lexis360

- Doctrine: legal commentaries on a legal issue

- Dalloz, Lexis360. Legal journals contain doctrine.

These sources are ranked as follows:

Directives, for example, are derived European law (apart from the founding texts and other treaties, charters or principles, and international agreements forming primary law), but they are binding legal acts. Any company operating in the sector will therefore have to comply with these texts. However, while they concern all EU countries (26 since the Brexit), they do not apply at the same time in all countries, nor in the same form. Of course, we can also look to European regulations, which apply directly and at the same time.

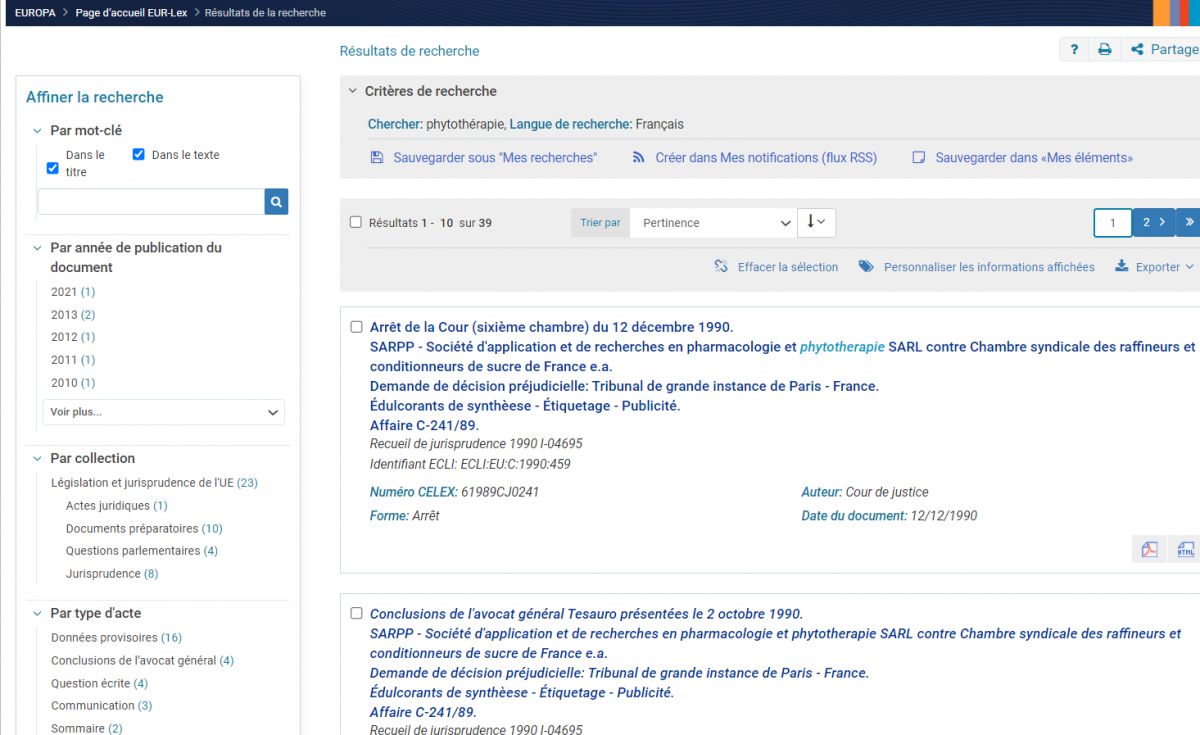

European legal texts are published in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU), which can be searched on the Eur-Lex website. Let's look for the directives that apply or will apply to our specific case, and the doctrine that will enable us to understand their effects.

Eur-Lex is freely available online, but to find commentaries and doctrine, you generally have to turn to subscription databases such as Lexis-Nexis.

A search on the term phytotherapy in Eur-Lex doesn't give too many results: 39 in a simple search on Eur-Lex. This will not be the case for all searches, so use the advanced search.

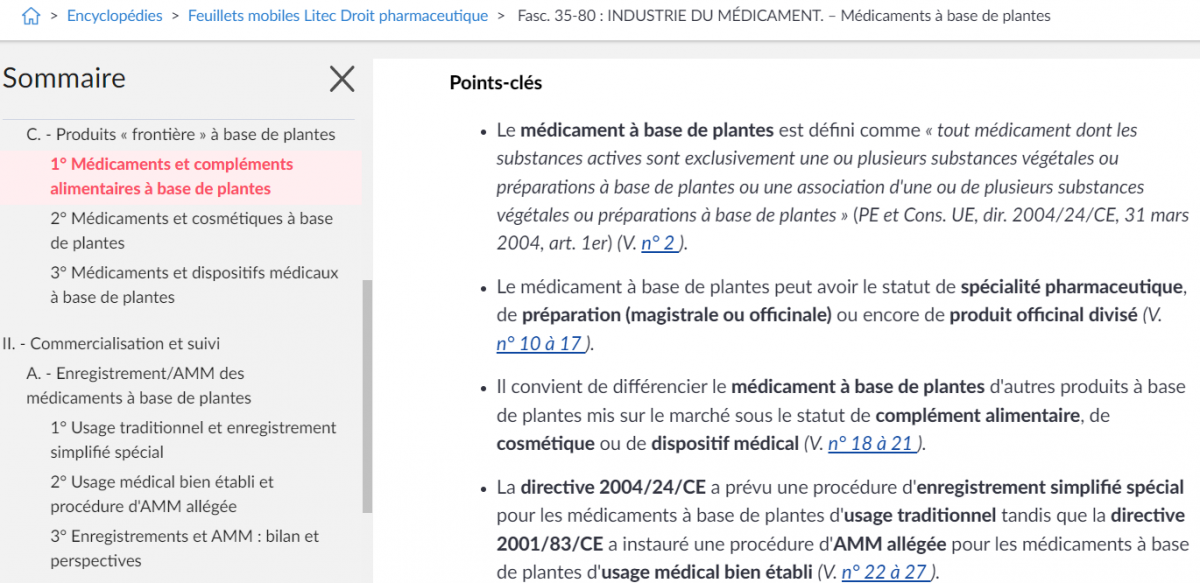

Browsing through these results does not give you an idea of the legislation applying to the herbal medicine sector in Europe, and more specifically in France. You will need to consult the Dalloz or Lexis databases, in the encyclopedia, summary or educational sheet sections, for a useful overview. However, the national law of countries other than France is not accessible via these databases.

|

3 main subscription-based resources accessible via the K-lab:

Our guide on legal information will help you find out:

|

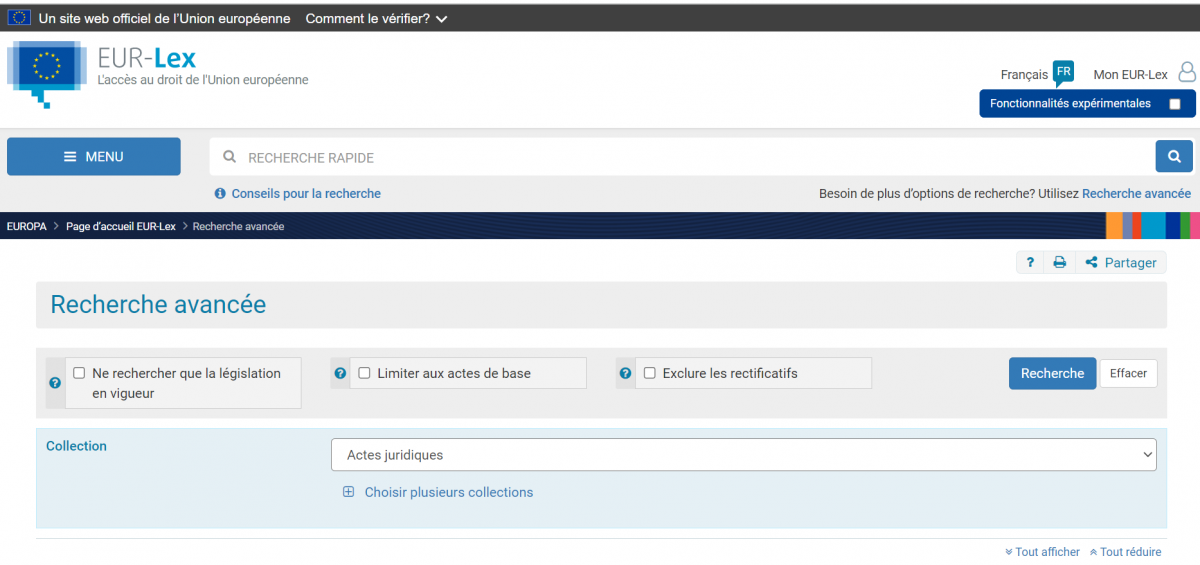

The first result of a simple search on Lexis Nexis, a “fascicule” (a set of coherent texts extracted from the Lexis-Nexis encyclopedic collections), will provide an overview of the subject::

We'll see which European directives apply in the phytotherapy sector:

If we now want to search for this text: Directive 2002/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 June 2002 on the rapprochement of the laws of the Member States relating to food supplements 66 (Text with EEA relevance) (OJ L 183, 12 July 2002, page 51), we can turn to institutional sites providing public access to (French, European) law:

- Légifrance

- Vie publique (fiches thématiques)

- Eur-Lex

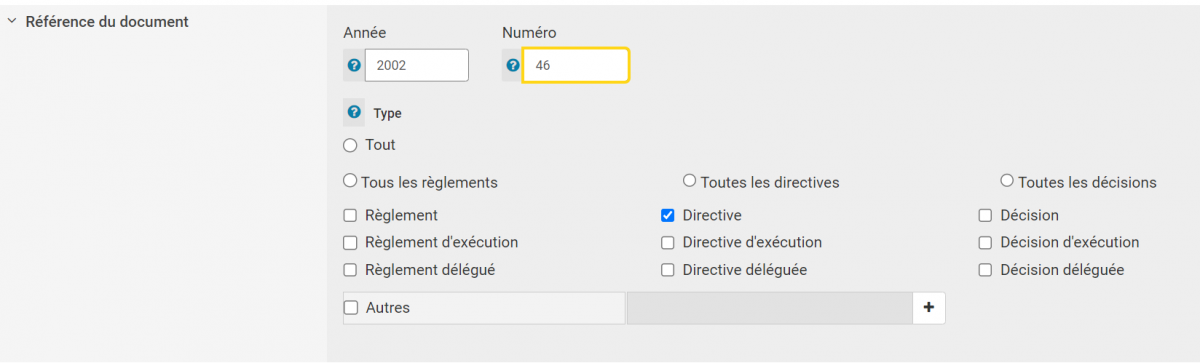

Here's how to carry out an advanced search for legal documents on Eur-Lex:

Tick the type of document Directive, indicating its year and number:

The only result we find is the directive we're looking for:

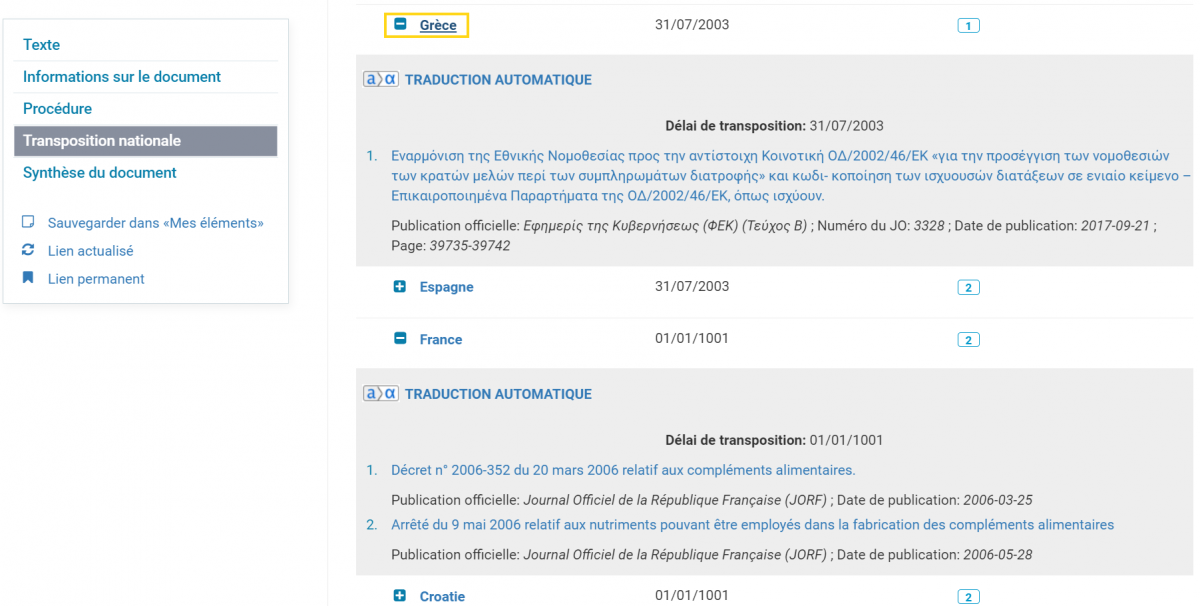

On the detailed directive sheet, we can consult its transposition by EU country, in particular France and Greece:

To complete this zoom, here is a list of legal abbreviations drawn up by the University of Toulouse.

Rate this content

How do I... - Monday 06 March 2023

Identifying Experts

Consulting an expert related to your research topic or your project is a relevant and necessary step. It allows you to benefit from a critical analysis or even advice concerning your approach or your recommendations.

However, this approach remains complex regarding the dilution of this notion in the media and social sphere: not a broadcast, not a debate without "expert" interventions, and social platforms such as LinkedIn are also echoing it.

For those who would like to solicit an expert, the challenge now is not to deal with the scarcity of profiles but rather to have the tools to identify the right one and thus separate the wheat from the chaff.

What is an expert?

A multidisciplinary notion / definition by practice

First, identifying an expert is being able to define what expertise is. This notion has a multidisciplinary dimension, it applies to different fields. Therefore, depending on whether you are a lawyer, a sociologist or a specialist in administrative law, you will not have (exactly) the same definition.

There is nevertheless a general consensus:

|

|

Cognitive and social dimension of the expert

The expert is the combined product of competence and legitimacy.

On the field of competence, they are at the intersection of the "specialist" (who possesses the professional or technical competence) and the "scholar" (who possesses the theoretical or academic competence). Their legitimacy is dual, namely:

- formal legitimacy (titles, diplomas and institutional recognition which are all strong signals). We are talking here about a designated/appointed expert.

- informal legitimacy (reputation, credibility, identity established in the community of reference, which are more like subjective criteria and faint signals). This is the emergent expert.

Evaluating/Qualifying an expert

Questioning the criteria that authenticate the quality of expertise.

It is from this double reading of competence/legitimacy that we can build a questioning process to assess the quality of the announced expertise; namely: "What characterizes the expertise of the person I am soliciting?":

|

|

These questions are the first good practice to be implemented to probe the quality of your interlocutor. It is a necessary step, but not sufficient.

The figure of the expert: watch out points

The principle of asking for the enlightenment of an expert - whether designated or emerging - on a given situation or subject is justified. However, there are some points to watch out for in order to sharpen your critical sense about this "figure". This perspective is all the more necessary in view of the increasing media attention they receives, which can lead to collusion and/or amalgams (a columnist or editorialist cannot be qualified as an expert).

In practice, you must pay particular attention to the posture and positions of the person you are soliciting:

|

A conviction is not an expertise: the self-assurance and composure with which the expert expresses themselves are no guarantee of the quality of the analysis. The expert is characterized by the ability to step back and accept doubt in their discourse. |

|---|---|

| One does not call oneself an expert : At a time of "personal branding" favored by social networks, we must remain vigilant about the effects of announcements and the CV of so-called experts. In the same vein, some people take up the (disputed) theory of the 10,000 hours which, according to K. Anders Ericsson, corresponds to the number of hours needed to excel in a field (see Malcolm Gladwell's book « Outliers, the story of success ») | |

| Expertise is generally attached to a specific field: an individual identified or announced as an expert focuses on a specific field, beware of "hyper or poly-experts". The media game can lead some people to express themselves in a field that is not their own. | |

| Expertise does not guarantee the accuracy of one's statements: elle nécessite une validation par les pairs. On peut prendre l’exemple ici de positions de certains microbiologistes et infectiologues durant la crise du Covid. Faire autorité n’est pas suffisant, vous devez confronter et vérifier les propos exprimés. | |

| it’s preferable that the expert is not "directly involved in the context of solicitation". An analysis will be all the more biased if the expert is involved. Step back from militant or lobbyist postures (be able to distinguish facts and opinions) | |

| Reactivity is not necessarily a guarantee of quality : be careful about individuals who are announced as experts and are quick to react to a news item or a situation. |

Going beyond media expertise |

|

Current information and communication practices are marked by the hegemony of social media and search engines, which favors the figure of the media expert, distinguished almost exclusively by the criteria of audience: number of views, likes, shares, etc.

The acceleration of media production processes, including newspapers and television stations that are well established in the media landscape, amplifies this phenomenon. In order to obtain a wide diffusion of a media, it is tempting to give even more audience to some personalities who already have some. It is therefore useful when looking for experts to be able to carry out some checks, and to use less dominant communication and information channels in order to be able to rely on a nuanced expertise.

|

(By the way) Who is seeking help from experts?

Your background also enters into the equation. Your level of knowledge on a topic inevitably influences the choice and quality of the expert. If you are more or less familiar with the subject you will have the capacity (or not) to evaluate the expert's method and the relevance of their analysis and results.. This is the “cognitive distance”, i.e. the gap between the two parties : you may have knowledge but you don’t have the necessary experience on the topic to apply your know-how and your soft skills. This difference, this distance then impacts the degree of trust between you and the expert. In the same vein, it is the cognitive distance that leads you to refer to faint signals (reputation) or strong signals (institutional recognition) in the choice of the expert.

Case study : identifying a financial market expert

Stéphane Cellier-Courtil's article is a perfect illustration of the best practices to implement in the process of identifying an expert. Here, the author describes his approach applied to the field of finance, a sector that can appear obscure to the uninitiated, which is why it is important to adopt a methodological approach.

The difficulty lies in the ability to mobilize the right interlocutor according to one's needs and the context.

- Bootz, J.-P., Lièvre, P., & Schenk, E. (2019). L’expert au sein des organisations: Définition et cadrage théorique. Revue internationale de psychosociologie et de gestion des comportements organisationnels, XXV(63), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.3917/rips1.063.0011

- Bootz, J.-P., & Schenk, E. (2014). L’expert en entreprise: Proposition d’un modèle définitionnel et enjeux de gestion. Management & Avenir, 67(1), 78–100. https://doi.org/10.3917/mav.067.0078

- Cellier-Courtil, S. (2019). Identification d’experts des marchés financiers. Revue internationale de psychosociologie et de gestion des comportements organisationnels, XXV(63), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.3917/rips1.063.0063

- Dubois, S., Mohib, N., Oget, D., Schenk, E., & Sonntag, M. (n.d.). Connaissances et reconnaissance de l’expert.

- Glatron, S. (1997). Qu’est-ce qu’un expert ? Vacarme, 3(3), 26–27. https://doi.org/10.3917/vaca.003.0026

- Les ambiguïtés de l’expertise. (1997). Vacarme, 3(3), 25–25. https://doi.org/10.3917/vaca.003.0025

- Xerfi. (n.d.). Olivier Sibony, HEC - A quels experts peut-on vraiment faire confiance ? - Stratégies & Management - xerficanal.com. Retrieved February 15, 2023, from https://www.xerficanal.com/strategie-management/emission/Olivier-Sibony-A-quels-experts-peut-on-vraiment-faire-confiance-_3750320.html

Rate this content

How do I... - Saturday 04 March 2023

The search for academic experts

After defining expertise and the key points to consider when looking for an expert in the Highlight on the keys to expertise, we will now focus on academic experts.

Nuancing the notion of expertise

Originally simple holders of “targeted competences [...] whose recognized practice allows them to enlighten judges on controversial cases", experts have become professionalized with the developments of the industrial society to take on an autonomy which seems to place them above other citizens. To such an extent that it is now necessary not only to distinguish the criteria of expertise in order to know how to evaluate it, but also to limit the recourse to expertise in order to preserve the "democratic process". The objectives of this Highlight are therefore twofold. Both to enable the effective identification of experts in an academic context, through a methodically conducted search for information, and to provide the keys to a critical evaluation of the place of expertise in decision-making.

Knowing how to delimit expertise according to its fields of application

Part of the difficulty in evaluating expertise is that it is not univocal. There are indeed many fields in which one cannot affirm that there is a better way of doing, thinking and deciding than another. These fields are subject to the coexistence and sometimes the confrontation of approaches, which must nevertheless at least be evaluated according to explicit criteria. The value of the selected expertise will then be conferred by the validity of the reasoning that led to its selection, in a socio-constructivist perspective of knowledge. Some fields of investigation, often more technical, suggest that the expertise can be demonstrated by the facts. Closer to a scientific approach, expertise then has a well-defined scope: it must be evaluated in the specific field where it is expressed and not be transposed to others. The aura of scientific knowledge among the general public and the media is indeed such today that it could also lead to a misuse of expertise.

To summarize parts 1 and 2 of this zoom, it is necessary to distance oneself from media trends in order to conduct an effective information search about experts in particular. This area is therefore related to the evaluation of information, and the notion of what is authoritative. In this regard, it is also important to remember that expertise is not fixed, that it is constructed in controversy. Knowing how to identify the points that are the subject of debate, and how to position the actors dynamically, in order to understand their interests, allows us to avoid being fooled by possible "strategies of doubt", such as greenwashing, or manipulations of all kinds that are part of disinformation.

Using experts in an academic context

In the context of higher education, the search for experts is most often carried out with the aim of identifying the main contributors to a field of knowledge, those who are at the origin of the concepts of this field or of its most advanced developments, in order to mobilize these concepts correctly in a professional thesis, a dissertation, or another academic assignment. Depending on the degree of technicality, the more or less industrial applications of these concepts, the ways of searching for experts in the field will differ. We will focus here mainly on this academic context

Web Of Science and Google Scholar for expert research

The search for authors who are specialists in a given field can be carried out on the academic databases Web of Science and Google Scholar, which are complementary.

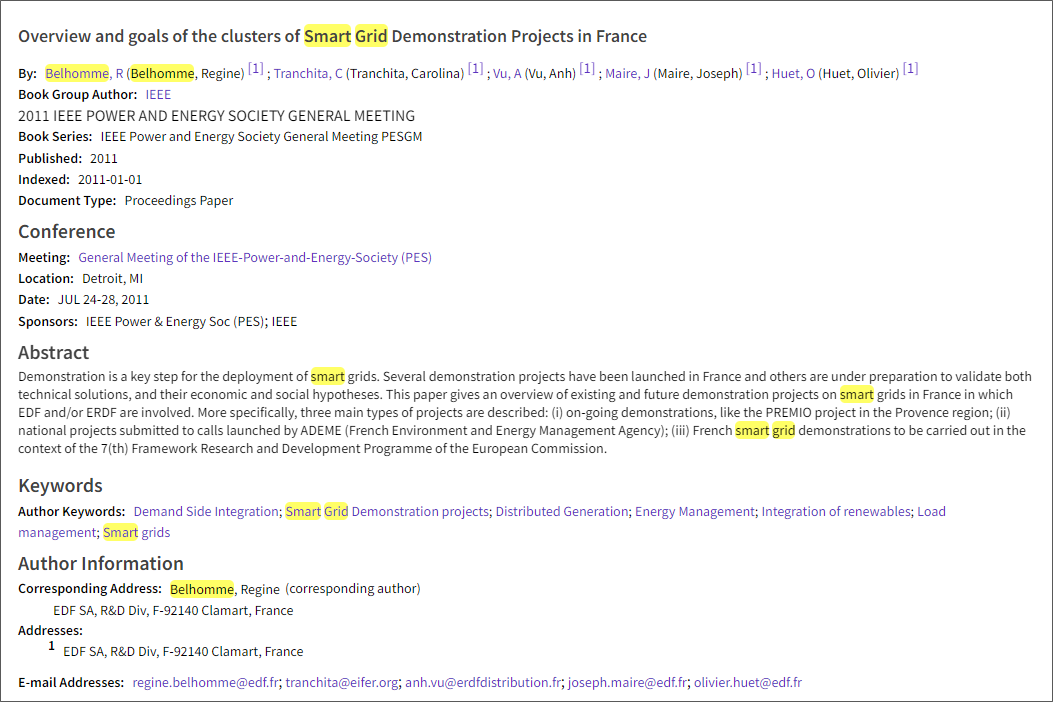

In any scientific article, it is difficult to identify a main contributor among the list of co-authors: it is necessary to use the contact information that is indicated, for example, in Web of Science:

The corresponding author is not necessarily the first author, but when it is, it gives a good indication of the main contributor of the article.

You can also rely on the various articles about the same field published by a scientific author to identify them as an expert in that field.

This type of search also applies to experts in the humanities and social sciences.

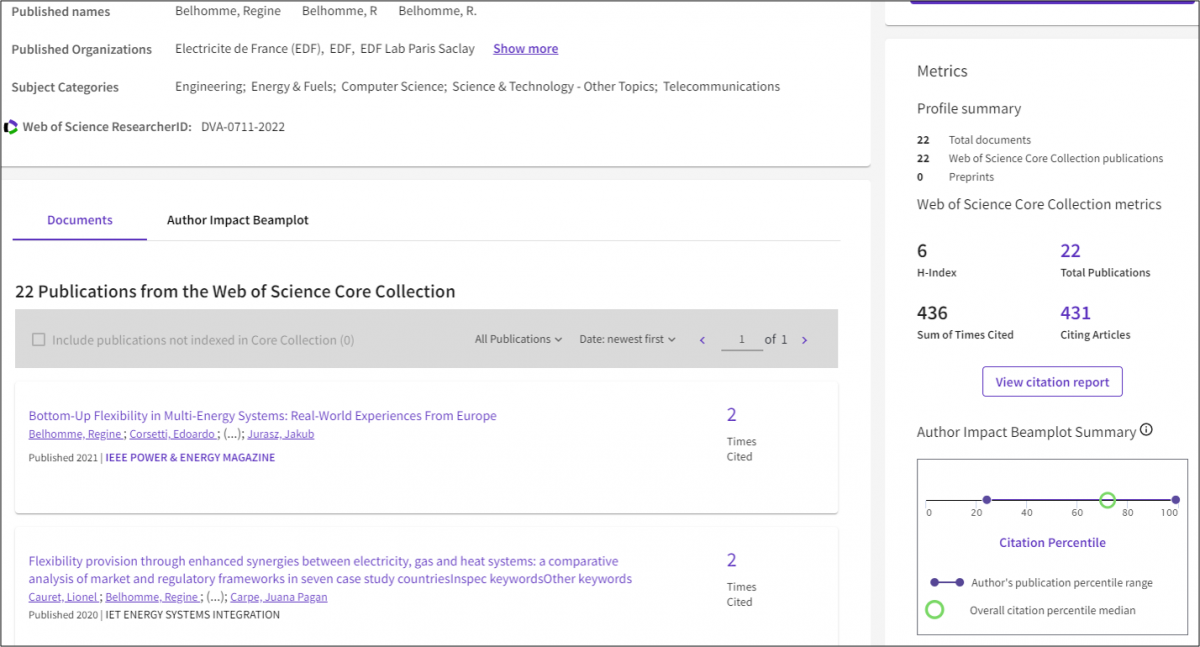

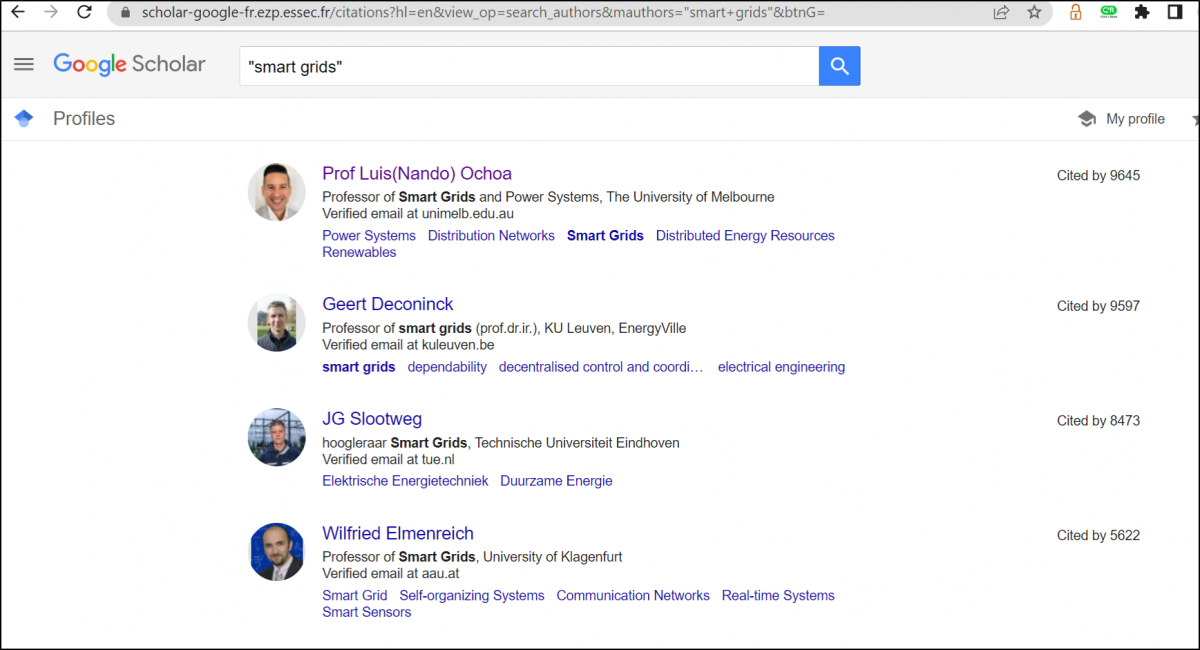

Two recent tools allow the identification of the most advanced contributors in a scientific and technical field:

- Google Scholar, through the researcher profile feature. This feature is not yet displayed by Google Scholar on its homepage, so you have to use the link provided above (Comment faire évoluer sa recherche d’information scientifique avec les nouveautés de Google Scholar et les autres ? Carole Tisserand-Barthole, 18 June 2022. BASES).

The most cited researchers appear first. The expert's record mentions their other subjects of expertise, as well as their articles in the decreasing order of the most cited, and their co-authors.

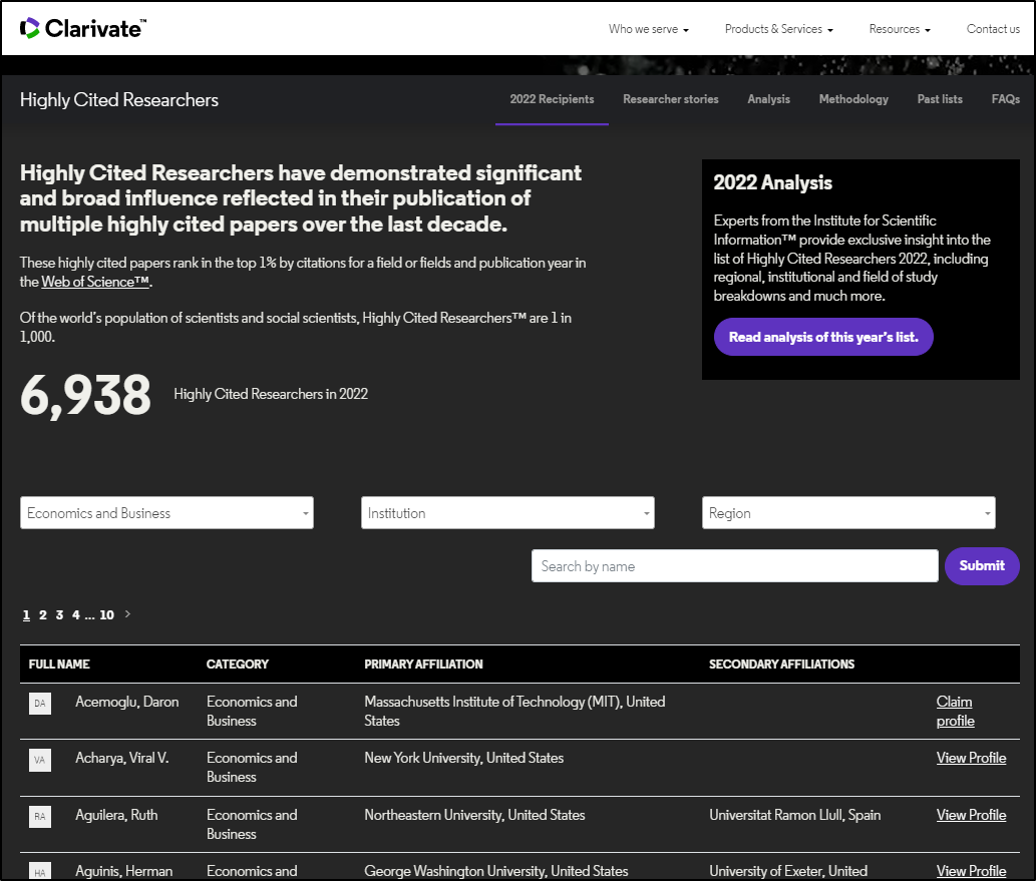

- Clarivate's ranking of the most cited researchers in the world by subject (more information about this ranking).

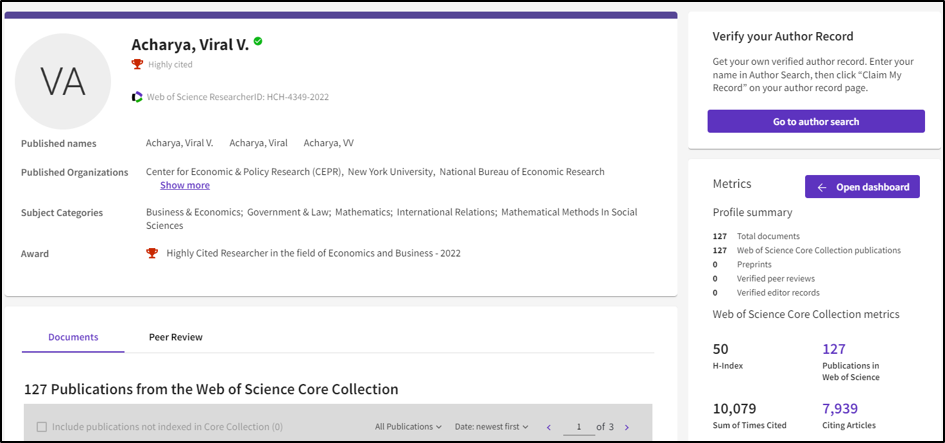

For example, you can search in the "economics and business" category, then by institution or region of the world, or directly by the name of a researcher to consult their profile:

You will then see on which subjects the expert intervenes the most, their publications in Web of Science and various other indicators accessible only via a subscription to the database, for example that of the K-lab of ESSEC.

But unlike Google Scholar Profiles, it is not possible to do a keyword search here.

Scientific social networks such as Academia or ResearchGate should be taken with caution because there is no filter for registering and submitting documents: always double-check with validated sources in our academic databases, especially peer reviewed journals.

You can also refer to the authors of textbooks, reference works in educational or popular science and technology collections.

Finally, you can verify the expertise of the people you have identified with your professors or tutors, who are themselves specialists in their field.

Rate this content

How do I... - Friday 20 January 2023

Right of diffusion of the K-lab documents

Can I copy a document to distribute it (documents from K-lab, Moodle or the Internet)? How do I know if I am respecting copyright?

Copyright can be seen as a "necessary evil" to encourage creation, before it can be appropriated by the public (F. Benhmaou, J. Farchy, Droit d’auteur et copyright, La découverte, 2007, p.112). It is also, in the broader context of intellectual property, an important economic issue. For example, copyright is particularly invoked by countries that are globally more exporters of content, but also by a few multinationals that concentrate the ownership of intellectual property rights on cultural content.

In this context, digital technology now makes copying much easier and more widespread, and therefore increases the risks of counterfeiting, in other words, of unauthorized copying. To summarize: "a new balance has to be found between the claims of those who want to take advantage of the potentialities of the Internet to widen their access to culture and the legitimate aspirations of authors and their rights holders to a "fair" remuneration” (Ibidem, p.56).

See below how the rules in force for the dissemination of K-lab and Internet documents are applied in respect of copyright.

May I, for example, distribute:

- in their entirety: a book? Course slides? A pedagogical case (ESSEC, Harvard...etc) A press article? An academic article (Open Access or not)? A market study?

Only if I have acquired the license for each copy.

A paper or electronic book available in two copies at the K-lab can only be used by two people at a time. It is forbidden to download or scan the entire paper book and put it online on the course website or send it by email to all students or participants.

Some publishers make it technically possible to download a chapter or the entire book. However, this does not give you the legal right to redistribute it.

A case study should be acquired in as many copies as there are students taking the course.

Or if it is an Open Access document. Their free license encourages dissemination on the contrary. But this should always be done with a reference to the source

Instead of distributing the document itself, I can distribute a hyperlink to the document. Anyone with access rights to the K-lab online resources will then be able to view it. This includes all students in diploma training, professors and administrative staff of the school.

As a reminder, it is forbidden to redistribute all course materials, including the pedagogical cases of course; a fortiori on external sites such as coursehero.

For exemple, this Springer book is available "unlimited" on the model of journal articles:

The PDF is downloadable for individual use, but may not be shared with others.

Similarly, this Ebsco ebook, available in a limited number of copies, should not be redistributed.

- a substantial portion of these materials?

Cursus that grant diplomas (not executive) benefit from an educational exception (read the Legal Framework of Educational Documents for more information). This means that they can broadcast an excerpt equivalent to 10% of a book (about one chapter) or 30% of a magazine issue (about one article), and 6 minutes of a film. This broadcasting can only take place within a very specific framework, that of a course in a degree program given by a non-profit organization, taught by a professor to his students. Course books, scores, music, videos and pictorial works are not concerned by the educational exception...

This educational exception is conditioned to the payment of a compensation by the training organization or its public supervisory body to the Centre Français du Droit de Copie, which then pays this compensation to the publishers.

For all other documents, it is necessary to be able to ask the author or their beneficiaries for permission to use a substantial part of his work.

Once again, Open Access documents, under a Free License, Creative Commons for example, can also be redistributed in the form of extracts, as long as the source is cited.

Applying these rules for sharing documents will allow our readers to:

- avoid infringing copyright and legal provisions that bind us to our content providers;

- know the rules that allow them to act in a broader context, respecting these rights;

- to protect their rights as a content producer, if any;

- to be aware of the economic value of the information;

- be aware of the socio-cultural value of the document in relation to the status of the author and more broadly the status of the content producer.

Rate this content

How do I... - Friday 06 May 2022

Evaluating information (part 2) : Awareness of Filter Bubbles and Media Economics

(Part 1 : Avoid cognitive biases and measure the reliability and relevance of the information)

The general media accessible to the general public, which you consult both for daily information and to feed your academic work, are almost all based on a liberal conception of information. Indispensable to the exercise of judgment by individuals in democracies and market economies, information must be accurate and verifiable. Its main disqualifying criterion is therefore false news, rumors.

However, we can qualify this as a somewhat idealized conception. Information is indeed not treated in the same way depending on whether it covers subjects that are important or not for the dominant economic and political interests in our societies. Individuals do not necessarily act in their own interest, but prove to be influenceable, and the presentation of the information that is made to them takes this into account.

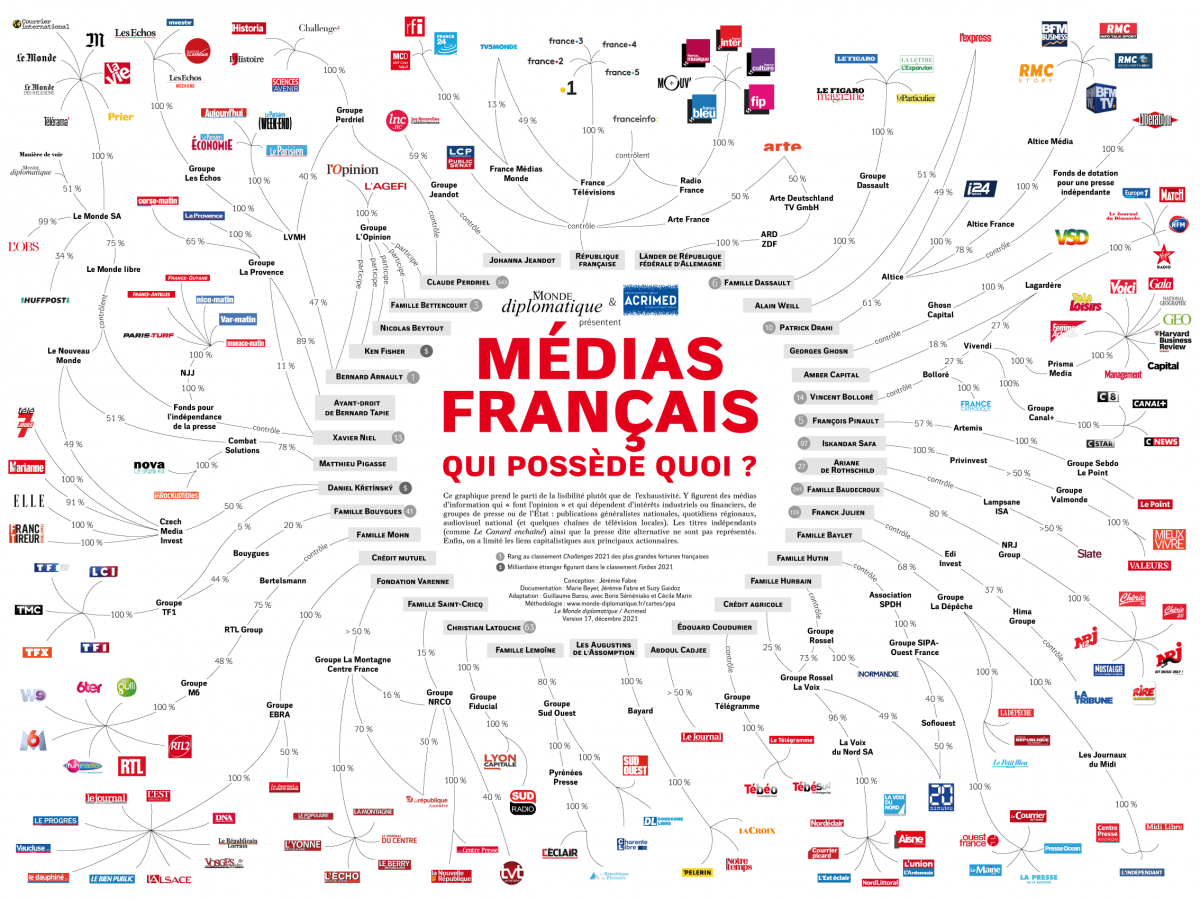

An interesting tool from a practical point of view to avoid these other possible biases of the information is the mapping of the big press and media groups, showing their owners, their resources. Do they depend more or less on advertising, on their readership, on public subsidies?

Source: Acrimed

This approach to the evaluation of information by its origin is similar to that of its production conditions. Is information the result of a long investigation by independent journalists, or is it generated in real time by freelancers working under the pressure of immediacy and a number of clicks to be generated? Digital technology has considerably reconfigured the production of information, due to the shift of advertising revenues from print and television to the web, to the benefit of intermediaries such as Google, rather than the producers of information themselves.

Since GAFAMs benefit from advertising all the more because it is profiled, the distribution of online information is therefore subject to distortions linked to audience generation as much as to the inevitable creation of "filter bubbles".

Eli Pariser has called this "filter bubble" the "universe of information unique to each of us" created by the constant adaptation of the content we see on the Internet to our preferences. This personalization is done through algorithms that cross-reference our past actions on the network with those of people who share some of our actions or characteristics, in order to predict what will interest us the most.

This filter bubble phenomenon is new in that it introduces three novel dynamics according to Eli Pariser:

- The strict isolation of the person in their filter bubble, in contrast to the media, which even when highly specialized, always have an audience composed of several people.

- The invisibility of the contours of the filter bubble, the opacity of the criteria that form it. Unlike the political orientation of a newspaper that it is possible to know, the Internet user does not know how, by what means, his information is personalized.

- The impossibility to choose whether or not to enter the filter bubble. Unlike a newspaper that one chooses to read, or a television channel to watch, the filtering of information on the Web is done without one being aware of it, and is increasingly difficult to avoid.

It is necessary to take this into account if you are looking for objective information of quality because it is the result of a rigorous journalistic work. Information whose primary goal is not to seduce in order to generate an audience, nor to go along with the particular beliefs of individuals in order to keep them on a network whose value grows with the number of users. There is obviously a stake in this for the public debate.

Thus, information can be evaluated according to its independence from real influences, and its potential to reveal phenomena that were previously poorly seen or ignored. It is not a question of looking for scoops, for which we know the risk of errors, but rather of clearing up new aspects of a reality, which are more difficult to make known because of the biases mentioned above, and of an approach similar to that of whistle-blowers. This approach to information is related to scientific ethics, because it is part of the paradigm of the search for truth.

Sources :

- Jm3, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Cognitive_Bias_Codex_(French)_-_John_Manoogian_III_(jm3).svg

- Bibliothèque de l'Université de Genève (2016). InfoTrack : Formation aux compétences informationnelles. https://infotrack.unige.ch/

- Brigitte Simmonot, Evaluer l’information, Documentaliste- Sciences de l’information, 2007, vol 44, n°3

- François-Bernard Huyghe (2019). 50 mots en stratégie de l'information. Le site de François-Bernard Huyghe. https://huyghe.fr/2019/02/18/50-mots-en-strategie-de-l-information/

- Jérémie Fabre, Marie Beyer (2022). Médias français : Qui possède quoi ? Acrimed | Action Critique Médias. https://www.acrimed.org/Medias-francais-qui-possede-quoi

- Eli Pariser, The filter bubble : how the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think, Penguin Publishing Group, 2011

- Samuel Lamoureux, La valeur de l’information sous le prisme de trois théories normatives du journalisme, Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication, mai 2021, n°2

Rate this content

How do I... - Friday 29 April 2022

Evaluating information (part 1): Avoid cognitive biases and measure the reliability and relevance of the information

During your documentary research and in general to learn about a field, you will constantly be required to evaluate the information. This is a key step in the documentary methodological approach, which can occur at different times during your research, depending on whether you already have the information available or whether it is the result of a whole research process that you have implemented.

In the first case, you start from a corpus that is already known, and need to verify its value: can you reasonably rely on the information you have to carry out your analyses, make your recommendations, present your syntheses, presentations, etc.? The methodological framework for identifying and reducing cognitive biases will then be your first tool for evaluating the information.

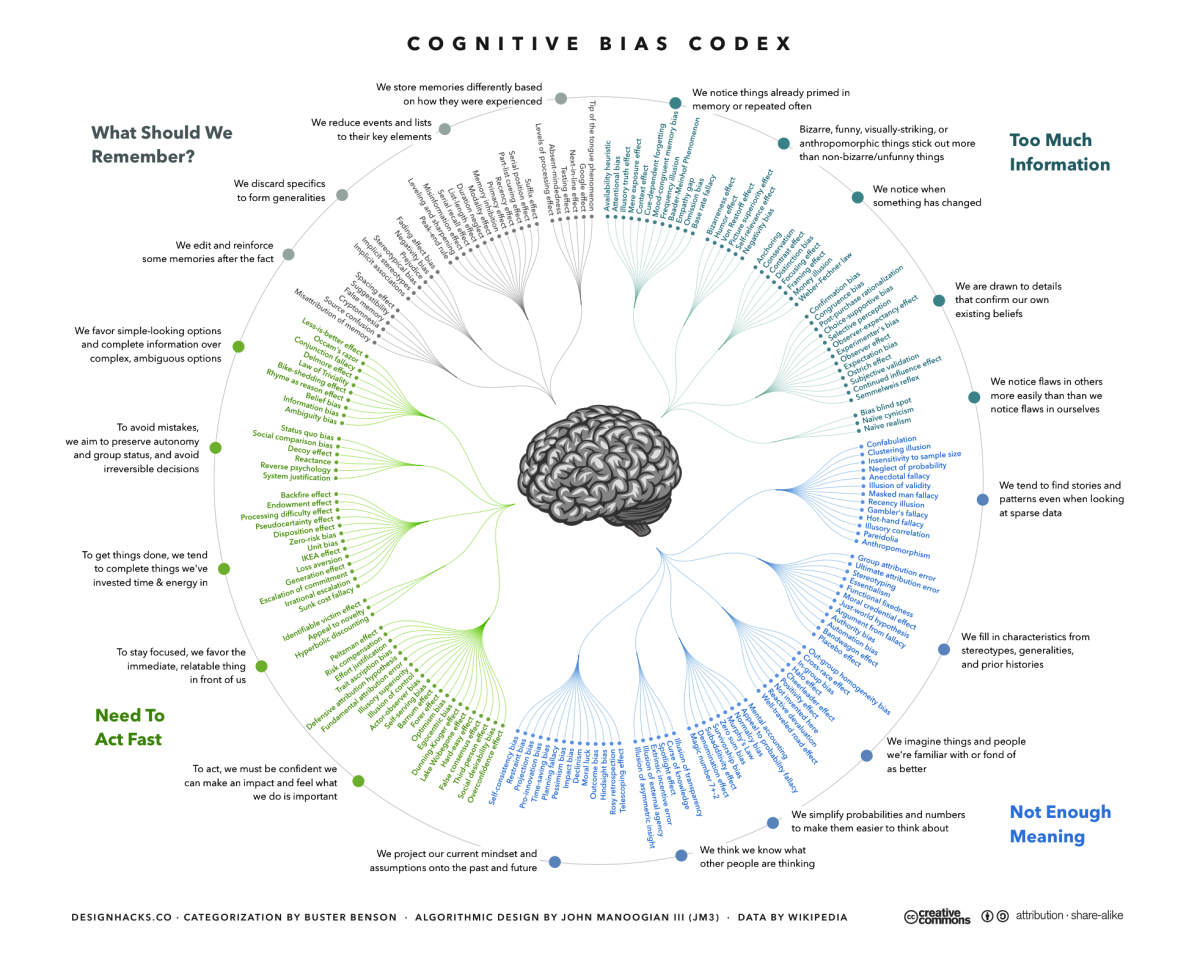

Being informed represents an effort, has a cost in terms of time and reflection in particular. It is easier to stay in one's comfort zone, and cognitive biases are there to help us! We tend to judge new information according to our previously acquired knowledge, questioning it as little as possible. We are also more inclined to believe the information that confirms our beliefs, etc. The diagram below goes into detail about the main cognitive biases we should stay aware of and avoid when searching for information.

Jm3, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the second case, the avoidance of cognitive biases will have already been implemented during the identification of your information needs, and will have helped you to determine what gaps to fill, corrective actions to bring, avenues to explore. At best, the evaluation of the information found will therefore be done on a corpus constituted by having already taken care to avoid cognitive biases. You can then apply other tools from other methodological frameworks. The first of these is the classic quality/relevance couple that can be summarized by the list of checkpoints below:

- Reliability: intrinsic quality of information

- Who is the author ? Their professional activity? Their possible institution of attachment? Are they recognized in their field of competence?

- What is the carrier of the information? A journal for the general public, professional or academic? An expert blog, an institutional site? What are its funding? Its audience? Its goals ?

- How old is the information? Is it sufficiently up-to-date for the field studied? Is the history of the concepts and phenomena presented taken into account? Is the information well located also on geographical, sociological perimeters, etc.?

- What is the form of the document? Journalistic, with the main facts stated first and probing in the body of the text? Academic, with an introduction setting out the objectives of the research and the methodology used, and a conclusion providing information on the main results?

- What links does the source allow? Are the cited references recognized in their field, do they open up new research perspectives? Via footnotes or endnotes, via the bibliography, can other useful sources be found?

- Relevance: usefulness of the information for a specific need

- Is the content covered related to all or part of my field of investigation?

- Is the level of precision the right one for my research? Neither too general nor too specific? Are the angle(s) of approach sufficiently varied and in-depth to cover my information needs?

- Depending on my specific need in terms of time, geography and other scopes, is the coverage offered by the source satisfactory?

- Will the style and form of the documents correspond to what is expected in my restitution: presentation, summary note, press review, market study, article, dissertation, professional thesis, etc.

- Do the additional sources accessible via the document consulted provide useful details for the research that is being done? Do they complete it?

These evaluation criteria are particularly important in the current context of the growing transition from the world of print, with its stable typology of documents resulting from a selective editorial process, to digital resources, giving access to fragments of information whose provenance is not always clearly visible. The second part of this highlight will focus on the specificities of the current informational context and its consequences on the evaluation of information.

Indeed, another methodological framework makes it possible to question what makes the value of an information from a more general point of view, not necessarily in order to produce a precise punctual result. But this reflection is not without relevance in a context of higher education, research, and citizenship training.

Rate this content

How do I... - Thursday 18 March 2021

How to create an alert with the Financial Times

You are monitoring information on a specific topic? It is possible to receive articles published in the FT directly in your mailbox.

The FT is a leading British business and financial daily. Please note that creating an ft.com account with the ESSEC form is required before creating an alert.

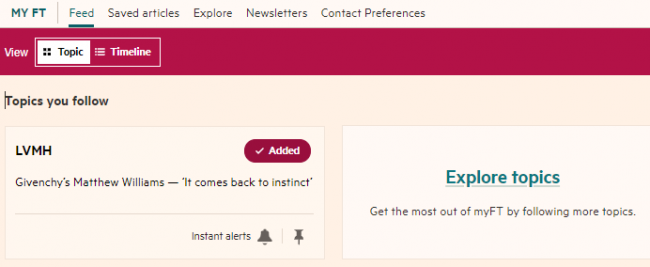

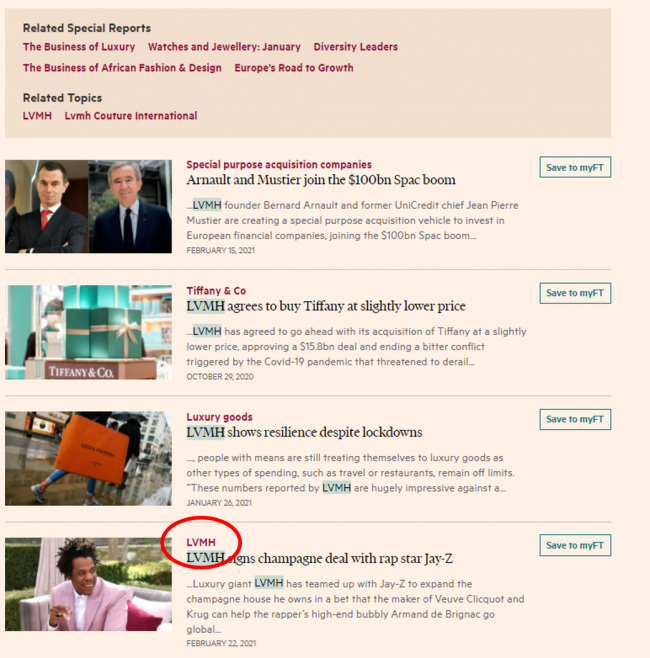

Once logged into your ESSEC ft.com account, it is possible to follow topics in order to receive weekly articles by email. It is also possible to set up your account to receive articles on the topics that interest you the most as soon as they are published.

First of all, you launch a search on the topic of your choice: company, personality, issue...

On the result page, click on the result being relevant for you, it appears in red when you can actually click on it:

Once on the related page, click on the "+ Add to myFT" button to add it to your myFT space:

When you go to your myFT space, you will see that the topic is there. By default, you will receive an email every Friday listing the articles on the topics you follow and that have been published during the week. It is possible to receive an email for each new publication by selecting the "Instant alert" option: