How do I... - Friday 22 September 2023

Searching for information with AI (Part 1): recommendations and search engines

The objective of this zoom is to communicate on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in a very general way, and on some of the functionalities it already provides for information research.

Definition of A.I.

Here we use two definitions quoted in the article “Defining artificial intelligence for librarians” :

- the OECD definition : "Artificial intelligence (AI) is ‘a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments. AI systems are designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy’". (OECD, 2020).

- and the European Commission's definition, which is also very general : "Simply put, AI is a collection of technologies that combines data, algorithms and computing power". (European Commission, 2020: 2).

To go beyond these simple definitions, you can consult the following works at ESSEC's K-lab:

|

Agrawal, Ajay Bansidhar. Prediction Machines : the Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2018. |

|

Crawford, Kate. Atlas of AI : Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021. |

And for a facilitated understanding of A.I. in relation to social issues, consult the free online guide:

|

Onuoha, Mimi and Nucera, Diana. A people's guide to AI. A People’s Guide Press, 2018 |

Possible uses of AI for information retrieval

The article “Defining artificial intelligence for librarians” cites three examples of AI applications in library services for their users.

- The first is the use of automated rankings and recommendations in metasearch tools such as Discovery.

- The second is the implementation of conversational robots to interact with library users, answering their questions and guiding them in the use of services and resources.

- The third use is the automation of scientific literature reviews in order to keep up with the scale and accelerating pace of publications.

These uses are not yet very widespread for reasons of cost and complexity of implementation, but the ESSEC Learning Centre is keeping a close eye on new tools and functions of this type.

Recommendations

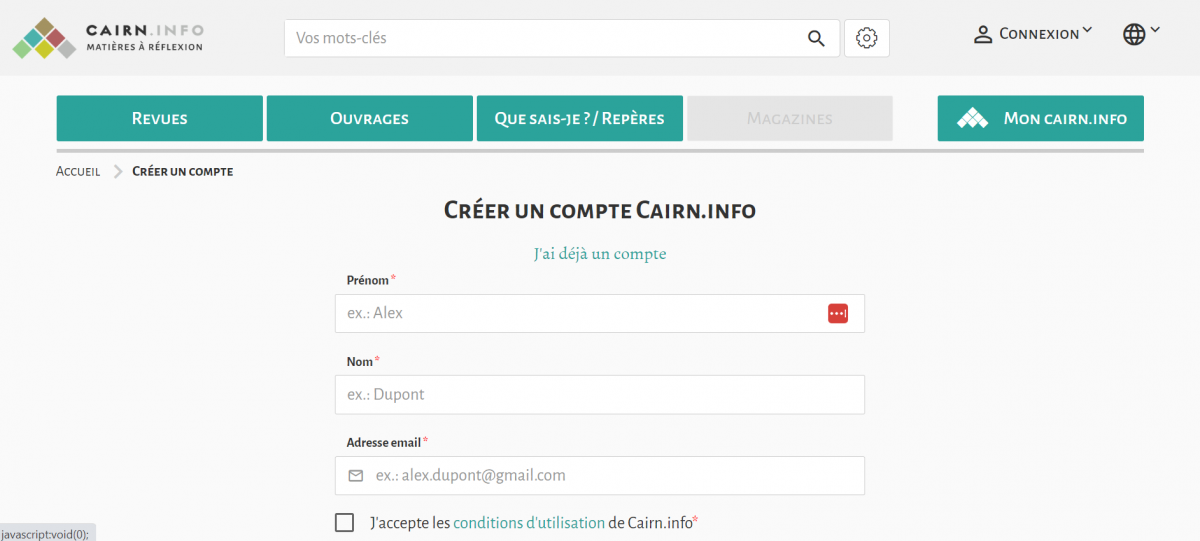

Recommendations have been part of the information landscape for several years. They are based on the analysis of recurring features in the document consultation paths of one or more people, in an attempt to predict what might meet their specific information needs. An example of the reasoned application of this type of technique is provided by the CAIRN database.

First of all, it should be pointed out that this recommendation service can only be accessed once an account has been created, which involves the management of personal data. So it's important to appreciate the value of a service that requires a counterpart that is far from trivial. In this sense, A.I. can put the spotlight even more firmly on ethical issues that were already being raised in social networks and free web services monetised by targeted advertising.

The recommendation criteria used by CAIRN are explicit and limited to a few, some of which can be configured by the user: semantic proximity, 'bounces' on authors referenced in publications already consulted, other articles read by readers of the same article as you. The information provider points out that "the algorithm cannot replace the human recommendation, drawn up by an expert in the discipline or field concerned.”

Search engines

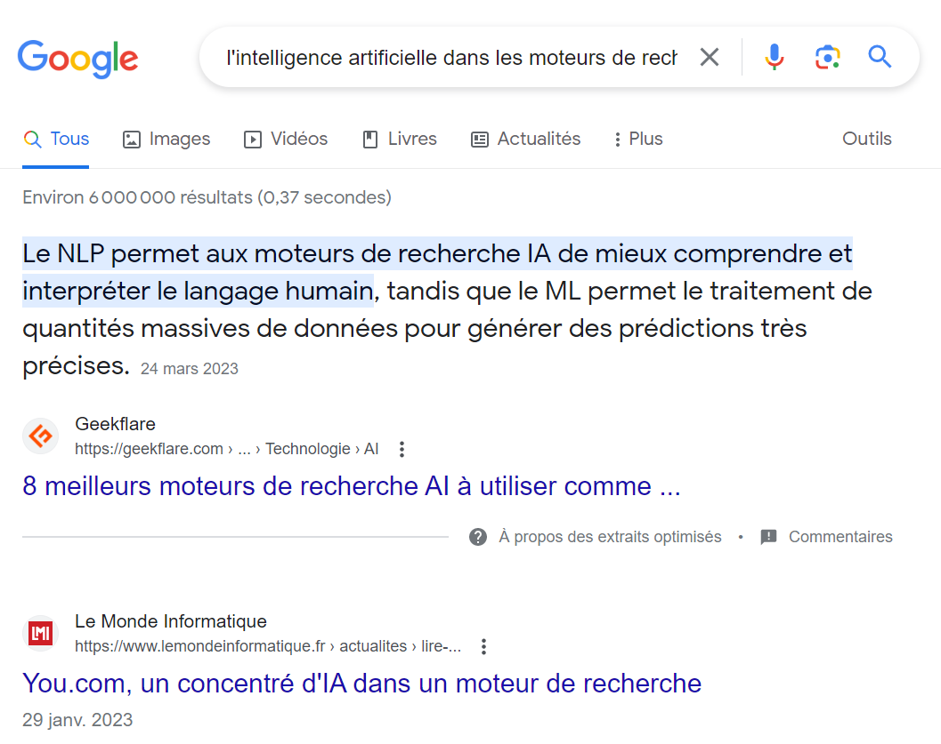

For several years now, search engines have been relying on machine learning to deliver the best answers to their users' queries. These queries tend more and more to be formulated in natural language, and less and less in combinations of keywords, search equations with Boolean operators or the equivalent of an advanced search with precise search fields. Nevertheless, this approach is still relevant.

The various uses of A.I. in search engines are aimed on the one hand at de-duplicating results and eliminating those that have no informational value, while at the same time classifying results in an order of relevance that is constantly evolving with new criteria. It is also useful for search engines such as Google to disambiguate the terms used, in order to better decipher natural language. A classic example is a search on the term "orange", for which it will be necessary to determine whether it refers to the city, the colour, the fruit, the brand, etc. This refinement of meaning enables the tool to try to "understand and detect the user's intention" when he enters his query in the search box. This increases the impression of relevance given by the results provided by the search engine, without even involving the famous conversational agents that are currently the talk of the town.

The second part of this highlight covers conversational agents.

Sources:

- “AI-Principles Overview - OECD.AI.” Accessed September 19, 2023. https://oecd.ai/en/principles.

- Anne-Marie. “Google n’est plus un moteur de recherche ni de réponses, mais un assistant virtuel.” Bases & Netsources. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.bases-netsources.com/articles-netsources/google-n-est-plus-un-moteur-de-recherche-ni-de-reponses-mais-un-assistant-virtuel.

- Cox, Andrew M., and Suvodeep Mazumdar. “Defining Artificial Intelligence for Librarians.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, December 22, 2022, 09610006221142029. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006221142029.

- Vathaire, Jean-Baptiste de. “Maîtriser l’algorithme pour favoriser les interactions : du bon usage des recommandations personnalisées. Utilisation et approche de l’IA par le portail Cairn.info.” I2D - Information, données & documents 1, no. 1 (2022): 50–56. https://doi.org/10.3917/i2d.221.0050.