How do I... - Friday 29 April 2022

Evaluating information (part 1): Avoid cognitive biases and measure the reliability and relevance of the information

During your documentary research and in general to learn about a field, you will constantly be required to evaluate the information. This is a key step in the documentary methodological approach, which can occur at different times during your research, depending on whether you already have the information available or whether it is the result of a whole research process that you have implemented.

In the first case, you start from a corpus that is already known, and need to verify its value: can you reasonably rely on the information you have to carry out your analyses, make your recommendations, present your syntheses, presentations, etc.? The methodological framework for identifying and reducing cognitive biases will then be your first tool for evaluating the information.

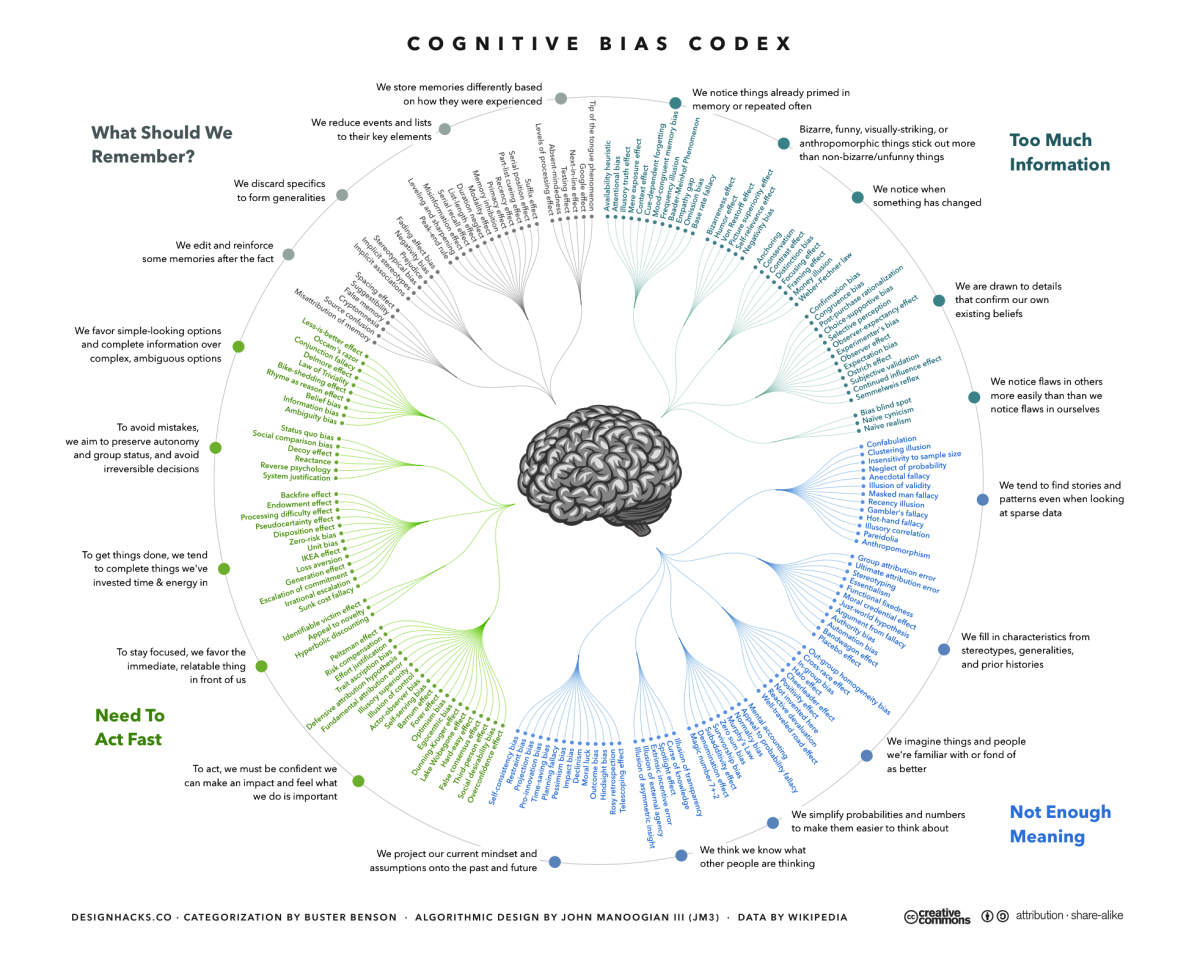

Being informed represents an effort, has a cost in terms of time and reflection in particular. It is easier to stay in one's comfort zone, and cognitive biases are there to help us! We tend to judge new information according to our previously acquired knowledge, questioning it as little as possible. We are also more inclined to believe the information that confirms our beliefs, etc. The diagram below goes into detail about the main cognitive biases we should stay aware of and avoid when searching for information.

Jm3, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the second case, the avoidance of cognitive biases will have already been implemented during the identification of your information needs, and will have helped you to determine what gaps to fill, corrective actions to bring, avenues to explore. At best, the evaluation of the information found will therefore be done on a corpus constituted by having already taken care to avoid cognitive biases. You can then apply other tools from other methodological frameworks. The first of these is the classic quality/relevance couple that can be summarized by the list of checkpoints below:

- Reliability: intrinsic quality of information

- Who is the author ? Their professional activity? Their possible institution of attachment? Are they recognized in their field of competence?

- What is the carrier of the information? A journal for the general public, professional or academic? An expert blog, an institutional site? What are its funding? Its audience? Its goals ?

- How old is the information? Is it sufficiently up-to-date for the field studied? Is the history of the concepts and phenomena presented taken into account? Is the information well located also on geographical, sociological perimeters, etc.?

- What is the form of the document? Journalistic, with the main facts stated first and probing in the body of the text? Academic, with an introduction setting out the objectives of the research and the methodology used, and a conclusion providing information on the main results?

- What links does the source allow? Are the cited references recognized in their field, do they open up new research perspectives? Via footnotes or endnotes, via the bibliography, can other useful sources be found?

- Relevance: usefulness of the information for a specific need

- Is the content covered related to all or part of my field of investigation?

- Is the level of precision the right one for my research? Neither too general nor too specific? Are the angle(s) of approach sufficiently varied and in-depth to cover my information needs?

- Depending on my specific need in terms of time, geography and other scopes, is the coverage offered by the source satisfactory?

- Will the style and form of the documents correspond to what is expected in my restitution: presentation, summary note, press review, market study, article, dissertation, professional thesis, etc.

- Do the additional sources accessible via the document consulted provide useful details for the research that is being done? Do they complete it?

These evaluation criteria are particularly important in the current context of the growing transition from the world of print, with its stable typology of documents resulting from a selective editorial process, to digital resources, giving access to fragments of information whose provenance is not always clearly visible. The second part of this highlight will focus on the specificities of the current informational context and its consequences on the evaluation of information.

Indeed, another methodological framework makes it possible to question what makes the value of an information from a more general point of view, not necessarily in order to produce a precise punctual result. But this reflection is not without relevance in a context of higher education, research, and citizenship training.