How do I... - Friday 06 May 2022

Evaluating information (part 2) : Awareness of Filter Bubbles and Media Economics

(Part 1 : Avoid cognitive biases and measure the reliability and relevance of the information)

The general media accessible to the general public, which you consult both for daily information and to feed your academic work, are almost all based on a liberal conception of information. Indispensable to the exercise of judgment by individuals in democracies and market economies, information must be accurate and verifiable. Its main disqualifying criterion is therefore false news, rumors.

However, we can qualify this as a somewhat idealized conception. Information is indeed not treated in the same way depending on whether it covers subjects that are important or not for the dominant economic and political interests in our societies. Individuals do not necessarily act in their own interest, but prove to be influenceable, and the presentation of the information that is made to them takes this into account.

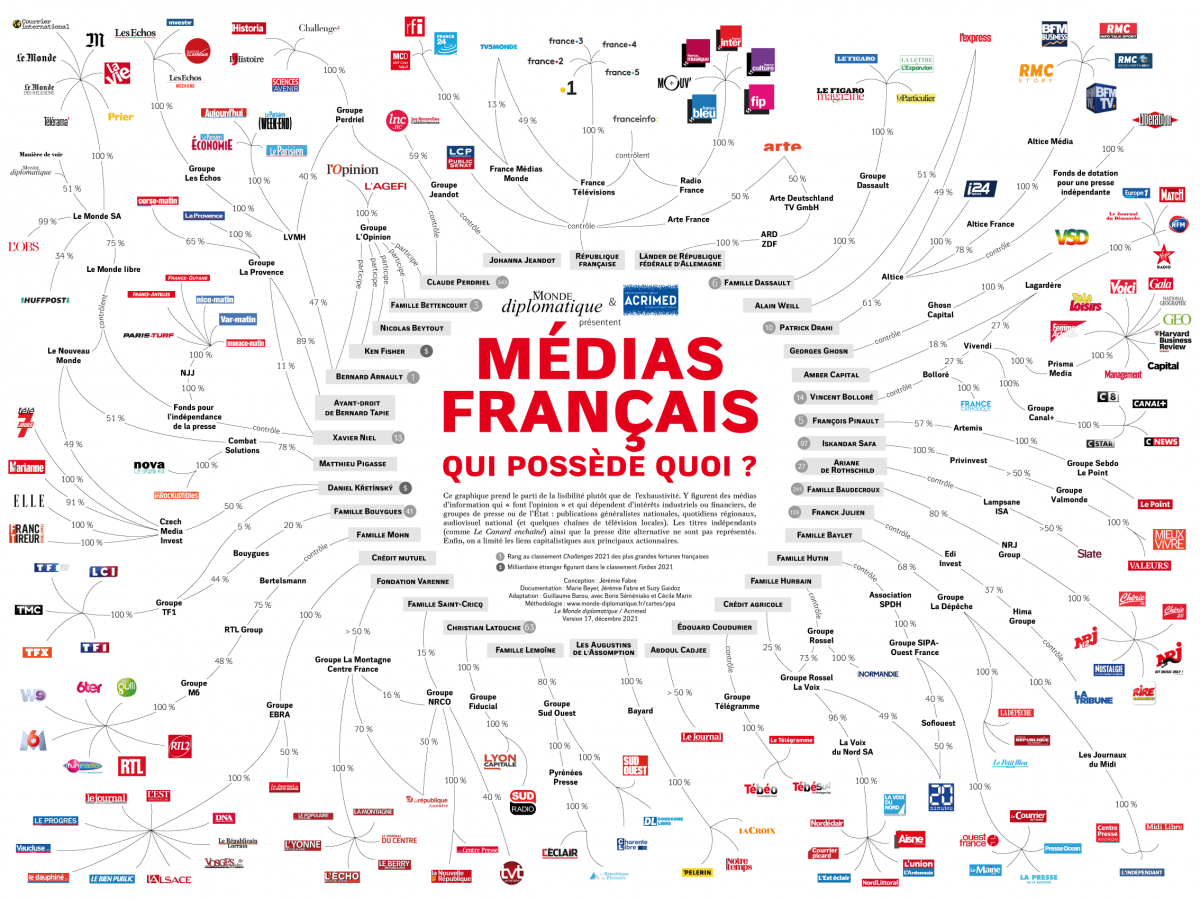

An interesting tool from a practical point of view to avoid these other possible biases of the information is the mapping of the big press and media groups, showing their owners, their resources. Do they depend more or less on advertising, on their readership, on public subsidies?

Source: Acrimed

This approach to the evaluation of information by its origin is similar to that of its production conditions. Is information the result of a long investigation by independent journalists, or is it generated in real time by freelancers working under the pressure of immediacy and a number of clicks to be generated? Digital technology has considerably reconfigured the production of information, due to the shift of advertising revenues from print and television to the web, to the benefit of intermediaries such as Google, rather than the producers of information themselves.

Since GAFAMs benefit from advertising all the more because it is profiled, the distribution of online information is therefore subject to distortions linked to audience generation as much as to the inevitable creation of "filter bubbles".

Eli Pariser has called this "filter bubble" the "universe of information unique to each of us" created by the constant adaptation of the content we see on the Internet to our preferences. This personalization is done through algorithms that cross-reference our past actions on the network with those of people who share some of our actions or characteristics, in order to predict what will interest us the most.

This filter bubble phenomenon is new in that it introduces three novel dynamics according to Eli Pariser:

- The strict isolation of the person in their filter bubble, in contrast to the media, which even when highly specialized, always have an audience composed of several people.

- The invisibility of the contours of the filter bubble, the opacity of the criteria that form it. Unlike the political orientation of a newspaper that it is possible to know, the Internet user does not know how, by what means, his information is personalized.

- The impossibility to choose whether or not to enter the filter bubble. Unlike a newspaper that one chooses to read, or a television channel to watch, the filtering of information on the Web is done without one being aware of it, and is increasingly difficult to avoid.

It is necessary to take this into account if you are looking for objective information of quality because it is the result of a rigorous journalistic work. Information whose primary goal is not to seduce in order to generate an audience, nor to go along with the particular beliefs of individuals in order to keep them on a network whose value grows with the number of users. There is obviously a stake in this for the public debate.

Thus, information can be evaluated according to its independence from real influences, and its potential to reveal phenomena that were previously poorly seen or ignored. It is not a question of looking for scoops, for which we know the risk of errors, but rather of clearing up new aspects of a reality, which are more difficult to make known because of the biases mentioned above, and of an approach similar to that of whistle-blowers. This approach to information is related to scientific ethics, because it is part of the paradigm of the search for truth.

Sources :

- Jm3, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Cognitive_Bias_Codex_(French)_-_John_Manoogian_III_(jm3).svg

- Bibliothèque de l'Université de Genève (2016). InfoTrack : Formation aux compétences informationnelles. https://infotrack.unige.ch/

- Brigitte Simmonot, Evaluer l’information, Documentaliste- Sciences de l’information, 2007, vol 44, n°3

- François-Bernard Huyghe (2019). 50 mots en stratégie de l'information. Le site de François-Bernard Huyghe. https://huyghe.fr/2019/02/18/50-mots-en-strategie-de-l-information/

- Jérémie Fabre, Marie Beyer (2022). Médias français : Qui possède quoi ? Acrimed | Action Critique Médias. https://www.acrimed.org/Medias-francais-qui-possede-quoi

- Eli Pariser, The filter bubble : how the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think, Penguin Publishing Group, 2011

- Samuel Lamoureux, La valeur de l’information sous le prisme de trois théories normatives du journalisme, Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication, mai 2021, n°2